“No player shall run with the ball.”

In a modest home in Barnes, London, the ink dried on a sentence that would split football in two — one path leading to rugby, the other to the global phenomenon we now know as soccer. The man behind the pen? Ebenezer Cobb Morley, a Victorian solicitor who never imagined that his sense of fairness and love for sport would ignite a revolution that would echo across centuries, continents, and cultures.

Morley didn’t roar like a captain or thunder like a striker. He was quiet. Measured. But in 1863, in the firelit glow of his study, he created order from chaos — and in doing so, handed the world a game.

From Hull to the Thames – The Making of a Gentleman Sportsman

Ebenezer Cobb Morley was born in Hull in 1831 to a nonconformist minister and a mother who insisted he carry her maiden name, Cobb, with pride. He grew up surrounded by ideals of discipline, decency, and public duty. These values would follow him like a shadow throughout his life.

At 23, he passed the bar and became a solicitor. But law alone didn’t fulfill him. He moved to London and settled in Barnes, a leafy suburb resting against the slow curve of the River Thames. It was there, among oars and foxhounds, that he began crafting a life shaped equally by logic and athleticism.

Morley rowed. He hunted. He kept a dozen beagles and organized local regattas. He was the kind of man who would draft a legal document by day and glide downriver at dawn, mist curling off the water, heart pounding with rhythm and motion.

A Game Without Rules – And a Man Who Couldn’t Stand Chaos

Football in the early 1860s was little more than a brawl with a ball. Each school, town, or gentleman’s club had its own version. Some allowed you to run with the ball in hand. Others banned it. Some glorified the brutality of hacking — deliberately kicking an opponent’s shins — as a test of manliness.

Morley saw opportunity in this chaos. In 1862, he founded the Barnes Football Club, one of the earliest football clubs open to public members, not just elite schoolboys. In a match against Blackheath, Barnes lost not just the game but their composure — unfamiliar with the other club’s rules, players clashed, and Morley himself was nearly injured.

That match stuck with him. He realized what football needed wasn’t passion — it had plenty — but rules. Not to constrain, but to unify. What cricket had with the Marylebone Cricket Club, football desperately lacked.

The Birth of the FA – And a Historic Change in Sport

In 1863, Morley penned a letter to Bell’s Life in London, a leading sports paper, proposing something radical: a single code for football, governed by an official body. It was an act of quiet rebellion against the chaos.

That October, representatives from London clubs gathered at the Freemasons’ Tavern. Morley stood among them — lawyer’s notes in hand, vision burning beneath his calm demeanor. There, The Football Association was born, with Morley elected as its first Honorary Secretary.

The debates were fierce. Should players be allowed to carry the ball? Should hacking be permitted as a test of grit? The room split — gentlemen arguing between the future of the sport and its rough past.

And then, in a moment of clarity, Morley withdrew his own draft of the rules and advocated instead for a set based on the clean, kick-only Cambridge rules. It was an act of humility and leadership.

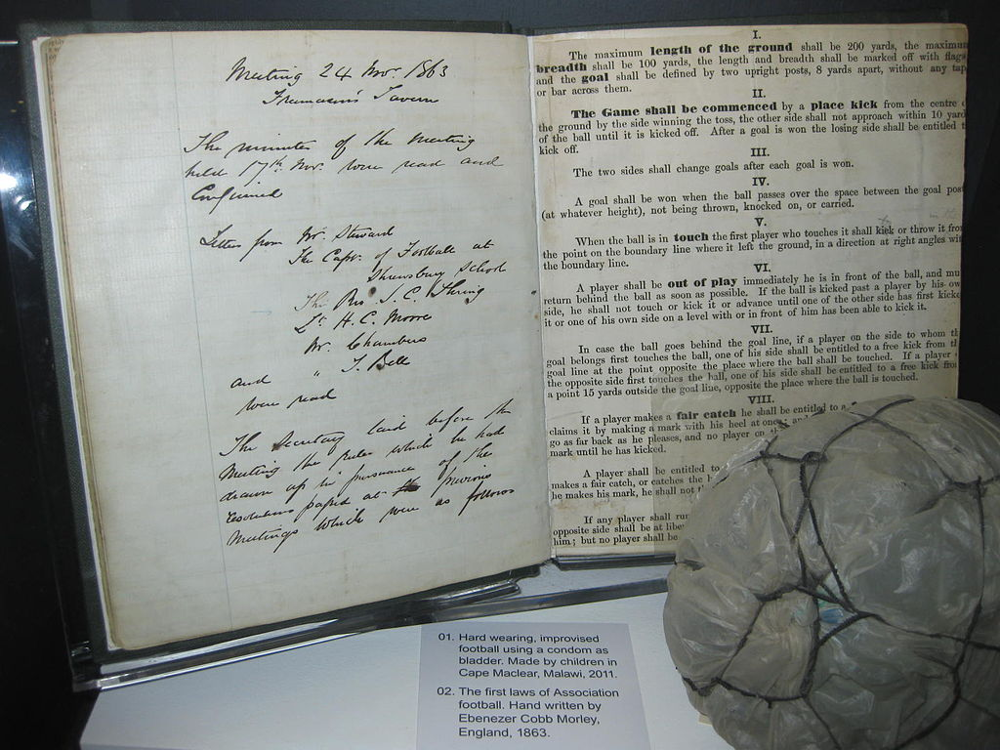

By December, they published the first 13 laws of football, and with them, gave birth to a game the world could recognize.

Writing the Laws of the Game – In Ink and Legacy

Morley’s handwriting still lives in the British Library — a simple, understated script that laid down ideas now understood by billions: no tripping, no carrying, goals at either end.

“No player shall run with the ball.”

That one line became the border between football and rugby. The code Morley helped craft became the skeleton for the world’s most-played sport. It was clarity made visible, passion made playable.

Trials, Triumphs, and the First FA Cup

The early years were hard. Clubs dropped out. Interest flagged. At one point, the FA nearly disbanded. But Morley, now President, held fast. He believed in what they’d started.

In 1871, under Morley’s presidency, the FA Cup was born — the world’s first official football tournament. When the Wanderers won the final in 1872, it was Morley who presented the trophy.

He had taken an idea from paper to pitch. From sketch to silver.

A Life Beyond Football – Rowing, Beagles, and Community Duty

Morley’s impact wasn’t limited to the field. He kept rowing well into his 80s, sculling daily on the Thames as a white-haired symbol of vigor. He organized regattas, encouraged youth sports, and mentored countless local athletes.

He was appointed a Justice of the Peace, represented Barnes on the Surrey County Council, and helped preserve the green commons where young boys — unknowingly — played by his rules.

Football Becomes the World’s Game – And Morley’s Vision Lives On

By the turn of the 20th century, football had exploded across Europe, South America, and beyond. FIFA adopted Morley’s code. The World Cup was born.

Today, over 250 million people play organized football. Every goal scored, every kick taken, is a distant echo of Morley’s pen scratching across parchment in 1863.

Rediscovering Morley – The Forgotten Founder Remembered

For years, his name was forgotten — lost beneath club banners and roaring stadiums. But in 2013, the FA honored him during their 150th anniversary. In 2018, Google gave him a doodle — a quiet thank-you from the digital age to a man of ink and paper.

His grave in Barnes Cemetery is simple. A small stone. A wreath of red roses shaped like a football crest was laid on it recently.

No fanfare. Just quiet remembrance. Just like Morley would have wanted.

Legacy: One Game. One Vision. One Man Who Gave the World a Ball and a Rulebook.

From the silence of a lawyer’s study came a roar that would shake the world.

Ebenezer Cobb Morley believed that games should be fair. That competition should unite. That rules could elevate chaos into art.

He didn’t seek fame. He didn’t profit. He simply saw what football could be — and wrote it down.

Today, every stadium, every match, every child chasing a ball under the sun carries his legacy.

And that is the most beautiful goal of all.

Image Placeholders

![Ebenezer Cobb Morley Portrait] – Alt: Portrait of Ebenezer Cobb Morley in later life with white mustache

![FA Meeting Reenactment] – Alt: Illustration of gentlemen at Freemasons’ Tavern in 1863, debating rules of football

![Barnes Football Field] – Alt: View of modern Barnes Common where Morley founded his club

![Morley’s Handwritten Rules] – Alt: Historic image of the original football rulebook

![Grave of Ebenezer Cobb Morley] – Alt: Simple gravestone in Barnes Cemetery, with football-themed wreath

FAQ

Q: Why is Ebenezer Cobb Morley called the Father of Modern Football?

He proposed the creation of the Football Association in 1863 and drafted the first official rules. His actions separated football from rugby and created a code that could be shared across clubs and countries.

Q: Did Morley ever play football himself?

Yes. He founded Barnes FC, played in early matches, and even captained teams under the new rules he helped write.

Q: How are Morley’s rules different from rugby?

Morley’s rules banned carrying the ball and outlawed rough physical play like hacking. This made football a kicking-based game, establishing it as a separate sport from rugby.

Q: How is he remembered today?

With commemorative plaques, a Google Doodle, and features in football museums — but most of all, by the billions who play the game he helped define.